Ever wondered what a raster image processor or RIP does? And what does RIPping a file mean? Read on to learn more about the phases of a RIP, the engine at the heart of your Digital Front End (DFE).

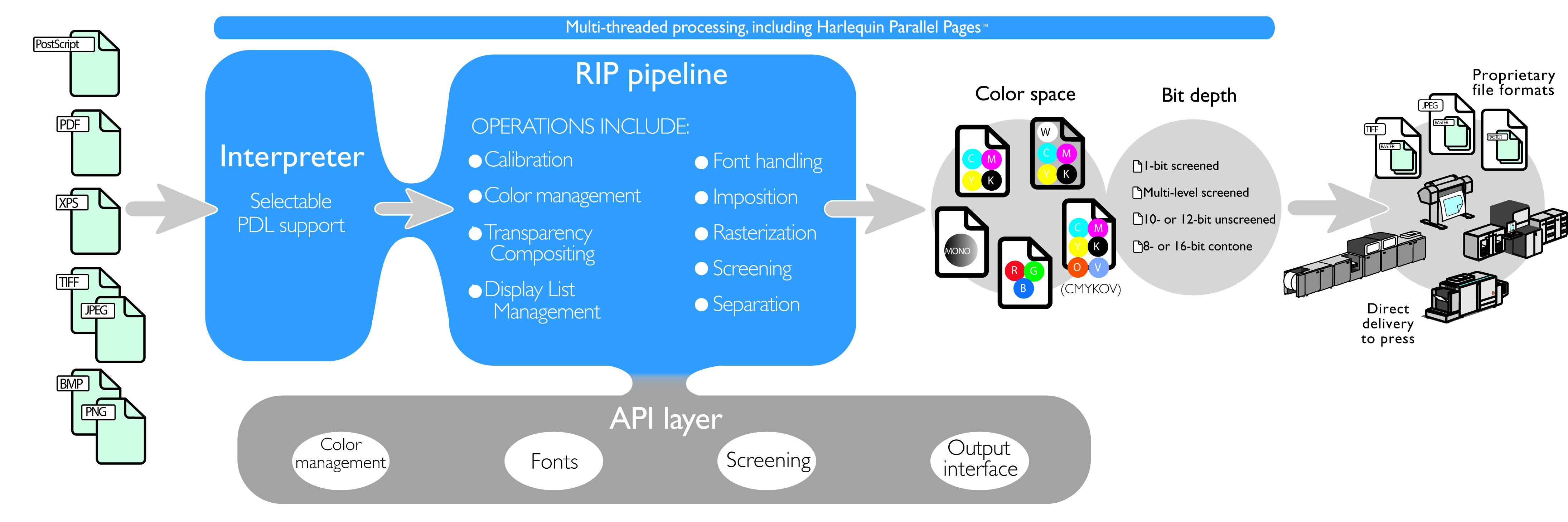

The RIP converts text and image data from many file formats including PDF, TIFF™ or JPEG into a format that a printing device such as an inkjet printhead, toner marking engine or laser platesetter can understand. The process of RIPping a job requires several steps to be performed in order, regardless of the page description language (such as PDF) that it’s submitted in. Even image file formats such as TIFF, JPEG or PNG usually need to be RIPped, to convert them into the correct color space, at the right resolution and with the right halftone screening for the press.

Interpreting: The file to be RIPped is read and decoded into an internal database of graphical elements that must be placed on the output. Each may be an image, a character of text (including font, size, color etc), a fill or stroke etc. This database is referred to as a display list.

Compositing: The display list is pre-processed to apply any live transparency that may be in the job. This phase is only required for any graphics in formats that support live transparency, such as PDF; it’s not required for PostScript language jobs or for TIFF and JPEG images because those cannot include live transparency.

Rendering: The display list is processed to convert every graphical element into the appropriate pattern of pixels to form the output raster. The term ‘rendering’ is sometimes used specifically for this part of the overall processing, and sometimes to describe the whole of the RIPing process.

Output: The raster produced by the rendering process is sent to the marking engine in the output device, whether it’s exposing a plate, a drum for marking with toner, an inkjet head or any other technology.

Sometimes this step is completely decoupled from the RIP, perhaps because plate images are stored as TIFF files and then sent to a CTP platesetter later, or because a near-line or off-line RIP is used for a digital press. In other environments the output stage is tightly coupled with rendering, and the output raster is kept in memory instead of writing it to disk to increase speed.

RIPping often includes a number of additional processes; in the Harlequin RIP® for example:

- In-RIP imposition is performed during interpretation

- Color management (Harlequin ColorPro®) and calibration are applied during interpretation or compositing, depending on configuration and job content

- Screening can be applied during rendering. Alternatively it can be done after the Harlequin RIP has delivered unscreened raster data; this is valuable if screening is being applied using Global Graphics’ ScreenPro™ and PrintFlat™ technologies, for example.

A DFE for a high-speed press will typically be using multiple RIPs running in parallel to ensure that they can deliver data fast enough. File formats that can hold multiple pages in a single file, such as PDF, are split so that some pages go to each RIP, load-balancing to ensure that all RIPs are kept busy. For very large presses huge single pages or images may also be split into multiple tiles and those tiles sent to different RIPs to maximize throughput.

To find out more about the Harlequin RIP, download the latest brochure here.

This post was first published in June 2019.

Further reading:

1. Where is screening performed in the workflow

2. What is halftone screening?

3. Unlocking document potential

To be the first to receive our blog posts, news updates and product news why not subscribe to our monthly newsletter? Subscribe here

Follow us on LinkedIn and Twitter